The Sun

All the stars, including our Sun, are gigantic balls of superheated gas, kept hot by atomic reactions in their centers. In our Sun, this atomic reaction is hydrogen fusion: four hydrogen atoms are combined to form one helium atom. The temperature at the core of our Sun is thought to be 36,000,000°F, or about 20,000,000°C, and the surface temperature averages 11,000°F, or about 6,000°C. The diameter of the Sun is 865,400 mi, and its surface area is approximately 12,000 times that of Earth. Compared with other stars, our Sun is just a bit below average in size and temperature, and is a yellow dwarf star. It is 4.5 billion years old, and its fuel supply (hydrogen) is estimated to be sufficient for another 5 billion years.

Our Sun is not motionless in space; in fact, it has two kinds of motion. One is a seemingly straight-line motion in the direction of the constellation Hercules at the rate of about 12 miles per second. But since the Sun is a part of the Milky Way system and since the whole system rotates slowly around its own center, the Sun also moves at the rate of 175 miles per second as part of the rotating Milky Way system.

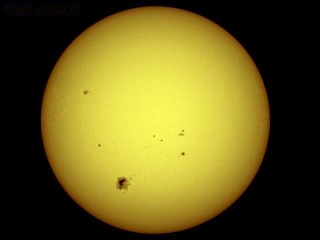

In addition to this motion, the Sun rotates on its axis. Observations of the motion of sunspots (darkish areas that look like enormous whirling storms) and solar flares, which are usually associated with sunspots, have shown that the rotational period of the Sun is just short of 25 days. But this figure is valid for the Sun's equator only; the sections near the Sun's poles seem to have a rotational period of 34 days. Since the Sun generates its own heat and light, there is no temperature difference between poles and equator.

In 1998, scientists saw for the first time that solar flares produce seismic waves in the Sun's interior that resemble those created by earthquakes. They observed a flare-generated solar quake equivalent to a 11.3 magnitude earthquake. It contained about 40,000 times the energy released in the great 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

What we call the Sun's “surface” is scientifically known as the photosphere. Since the whole Sun is a ball of expanding hot gas, there is really no such thing as a surface; it is a question of visual impression. The layer outside the photosphere is known as the chromosphere, which extends several thousand miles beyond the photosphere. It is in steady motion, and often enormous prominences can be seen to burst from it, extending as much as 100,000 mi into space. Outside the chromosphere is the corona. The corona consists of very tenuous gases (essentially hydrogen) and makes a magnificent sight when the Sun is eclipsed.

In addition to heat and light, the Sun also generates solar wind, a stream of ionized particles that radiates outward through the solar system at high speeds. One of the effects of solar wind is that it forces the tails of comets to point away from the Sun. The solar wind also interacts with Earth's magnetic field, causing the auroras and other phenomena. Solar flares—eruptions of hydrogen gas on the surface of the Sun—can also cause disturbances in Earth's magnetic field.

As the Sun ages, it gradually expands and heats. It is estimated that the Sun's brilliancy will increase by 10% over the next 1.1 billion years or more, and, in about 6.5 billion years, our aging star will have doubled its present luminosity. The extreme heat generated will be catastrophic for Earth: the oceans will boil away and life as we know it will end. Eight billion years from now, the Sun's radius will extend beyond the present orbit of Venus, causing the total destruction of Earth.

The Milky Way Galaxy.  Copyright 1990 Hansen Planetarium, Salt Lake City, Utah. Reproduced with Permission. |