Defining Hate Crimes

No longer a Black and White issue

by Ricco Villanueva Siasoco |

This article was posted on August 18, 1999.

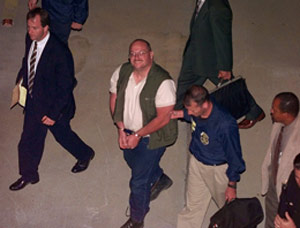

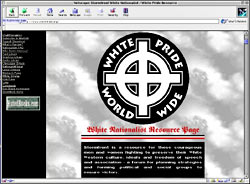

Buford O. Furrow opened fire at a Jewish community center. The avowed White supremacist will be prosecuted for hate crimes. "What is really being punished, as [critics] see it, is a criminal's thoughts, however objectionable they may be. The actions - incitement, vandalism, assault, murder - are already against the law." — Clyde Haberman  The Internet has enhanced communication between isolated hate groups. Related Links |

and righteousness like a mighty stream."

These powerful words were uttered by Martin Luther King, Jr. in the midst of the racial unrest of the 1960s. Decades later, it seems the unrest of that period has resurfaced—but this time with a broader target. Last week's rampage on a Jewish community center in Los Angeles reminds us that crimes once driven solely by hatred for one's race now stem from opposition to one's religion, gender, disability, or sexual orientation.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, a non-profit organization which tracks hate crimes, there were over 500 hate groups operating in the U.S. in 1998. The Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles tallies even more, monitoring over 2,100 hate sites on the Internet.

The term "hate crime" is a part of our everyday vernacular. But what's the definition of a hate crime? What are the issues facing legislators, law enforcement officials, and the American public?

More importantly, why the proliferation of these violent crimes?

Seeking a definition

The dictionary defines a hate crime as "any of various crimes... when motivated by hostility to the victim as a member of a group (as one based on color, creed, gender, or sexual orientation)." But the term doesn't always carry a commonly understood meaning.

In the on-line magazine Slate, Eve Gerber writes, "The definition of a hate crime varies. Twenty-one states include mental and physical disability in their lists. Twenty-two states include sexual orientation. Three states and the District of Columbia impose tougher penalties for crimes based on political affiliation."

Evolution of hate crimes

In Hate Crimes: Criminal Law & Identity Politics, authors James B. Jacobs and Kimberly Potter recount the introduction of the term hate crime in 1985, coined in legislation centered around the Justice Department's collection of "hate crime statistics." The media picked up on the term and quickly began to write about an epidemic before these statistics had even been gathered.

Current legislation allows federal prosecution of a hate crime only if the crime was motivated by race, religion, national origin, or color. In addition, the assailant must intend to prevent the victim from exercising a federally protected right. The Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 1999, passed by the Senate in July 1999, seeks to expand federal jurisdiction over these crimes.

Controversial legislation

Dissenting opinions mar even a seemingly black and white issue such as hate crimes. Jacobs and Potter argue that hate crimes legislation is redundant, as these offenses are already punishable under the law.

Clyde Haberman of The New York Times described the views of hate crimes critics in a recent column. "What is really being punished, as they see it, is a criminal's thoughts, however objectionable they may be. The actions - incitement, vandalism, assault, murder - are already against the law."

Understanding perpetrators, victims

Last year the American Psychological Association issued the report Hate Crimes Today: An Age-Old Foe in Modern Dress. In the report Dr. Jack McDevitt, a criminologist, stated, "Hate crimes are message crimes. They are different from other crimes in that the offender is sending a message to members of a certain group that they are unwelcome."

The National Institute of Mental Health has funded the first major study of the consequences of hate crimes on victims, narrowing in on anti-gay hate crimes. Preliminary research indicates that hate crimes have more serious psychological effects than non-bias motivated crimes.

Lone wolves, strong packs

Understanding the nature of those who commit hate crimes may be the most difficult aspect to grasp. Contrary to the notion of hate group conspiracies, most offenders act as lone wolves: small cells, pairs, or individuals acting alone.

Identifying individuals planning hate crimes is a formidable task. One common trait is membership in a hate organization. The majority—and perhaps most recognizable—are fringe neo-Nazi or Ku Klux Klan groups, but some organizations such as the Council of Conservative Citizens (CCC) have reached a level of positive acceptance. At a recent CCC's national conference, Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott— whose support of hate crimes legislation falters only because of its inclusion of homosexuality—was a keynote speaker.

In fact, a copy of Hunter, a novel by William Pierce (the leader of the neo-Nazi National Alliance) was found with the belongings of Oklahoma City bomber McVeigh. Pierce, like others involved with hate groups, has cultivated ties with other white American ethnic groups within our borders and abroad.

The Internet has undeniably contributed to alliances among these hate groups. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center's estimates— more modest than the Simon Wiesenthal Institute's— hate sites rose from 163 web sites in 1997, to 254 in 1998.

Where do we go from here?

Changes in hate crime legislation— whether viewed favorably or negatively— are simmering. The Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 1999 was passed by the Senate, and awaits a vote in the House.

In the words of Vice President Al Gore: "We must send a clear and strong message to all who would commit crimes of hate: it is wrong, it is illegal, and we will catch you and punish you to the full force of our laws."