The Supreme Court: Taney Court, 1837 to 1864

Taney Court, 1837 to 1864

Chief Justice Roger Taney had the difficult position of following the true star of the Court. Not an easy act to follow. Many feared he would try to overturn much of Marshall's work building the stature of the court, especially because of this sentence he wrote about the Supreme Court during a controversy involving the Bank of America, “the opinion of the judges has no more authority over Congress than the opinion of Congress has over the judges, and on that point the President is independent of both. The authority of the Supreme Court must not, therefore, be permitted to control the Congress or the Executive.” If he followed through on this belief, he would overturn the Marshall decisions that strengthened the Court.

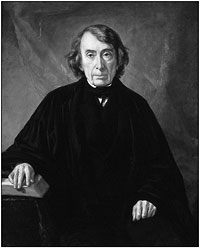

Official portrait of Chief Justice Roger Taney painted by George P. A. Healy.(Photography by Vic Boswell from the Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States)

Supporters of what Marshall accomplished feared the court was doomed, but these fears proved unwarranted because judicial restraint ruled the day and the Taney Court was reluctant to overturn precedents set by the Marshall Court. The primary contribution of the Taney Court to the foundation of U.S. law was the belief that property should not be secondary to the needs of man.

Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge

Living Laws

In Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge the Taney Court established a key principal that drives property decisions today: Property rights must, when necessary, be secondary to the needs of the community. Today this decision placing community needs over personal property rights still stands as a key precedent in cases involving personal property versus local needs. We most often see this precedent come to life when people must sell their property to a government entity, frequently at reduced market value, to make way for road construction, water projects, and other needs of the community.

One landmark case that reinforced that belief was Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge. The Charles River Bridge was run by a corporation held by Harvard College and some of Boston's leading citizens. The corporation ran a toll bridge over the Charles River in Boston based on a charter granted in 1785. The bridge owners made huge profits and the stock in the corporation rose tenfold.

The public was outraged by the monopoly granted this small group of people and in 1828 the Massachusetts legislature granted a charter for a second bridge over the Charles River to the Warren Bridge Company. The second charter mandated that the new bridge would become a free bridge shortly after construction. A free bridge, of course, hurt the business of the Charles River Bridge Corporation, so they filed suit claiming that the legislature had broken its contract, which the corporation believed had prohibited the construction of another bridge. The case made it to the Supreme Court for oral arguments on January 24, 1837.

In its decision handed down on February 12, 1837, the Taney Court held that property rights must, when necessary, be secondary to the needs of the community. The Court decided that the legislature did not give exclusive control over the waters of the river nor did it invade corporate rights by interfering with the company's ability to make a profit. The Taney Court's decision was critical to the country's need for encouraging economic development. In this case the new bridge met the community's need for finding new channels for travel and trade.

This case was just one of many decided during the years of the Taney Court that established the rights of corporations, as well as the limits that could be put on those rights. His court was the first to rule that corporations could operate outside the state in which they were chartered. It also set the groundwork for the legal theory that a corporation is on the same footing as a person when taken to court.

Dred Scott v. Sandford

Just the Facts

No one is certain what drove the Scotts to finally file suit for their freedom, but on April 6, 1846, Dred Scott and his wife Harriet filed suit against Irene Emerson. Three reasons have been given as possibilities—that they didn't like being hired out, that Mrs. Emerson was planning to sell them, or that he offered to buy out his family's freedom and was refused. Many believe that friends in St. Louis who opposed slavery encouraged Scott to sue for his freedom. Missouri courts had ruled in the past in favor of the doctrine “once free, always free.” Because Scott had lived in the free territories, he counted on those past rulings when he filed.

The first 20 years of the Taney Court showed to all its critics that they were wrong to think Taney would work to diminish the stature of the Court. Then a case that will live in infamy did diminish the Court when it made it to the Supreme Court's doorstep in 1857—Dred Scott v. Sandford, a case that ultimately hastened the start of the Civil War.

The case started in 1846, when a 50-year-old slave named Dred Scott filed suit for his freedom and the freedom of his wife. At that time, some areas of the country permitted slavery, while others prohibited it. Scott was purchased from a family named the Blows when they were living in St. Louis by Dr. John Emerson, who was a military surgeon.

While Emerson owned him, Scott moved with his new owner to posts in the free territories where slavery was prohibited. While in the free territories, Dred Scott married Harriet Robinson, who was also a slave and had two children, Eliza and Lizzie. He never challenged his status as a slave while living in those territories. In 1842, the Scotts returned to St. Louis with Dr. Emerson and his new wife Irene. Dr. Emerson died in 1843 and Irene started hiring out Dred Scott, his wife and their children.

Court Connotations

The Missouri Compromise was the brainchild of Henry Clay. Missouri was admitted as a slave state, while at the same time Maine was admitted as a free state. This kept the balance of 12 free states and 12 slaves states. As future states were added over the next 30 years, the balance had to be kept with one free state and one slave state admitted at the same time. States north of the 36 degrees 30 minutes north latitude, which was the southern boundary of Missouri, were free states. States south of that line could decide for themselves.

By that time the Scotts had lived in the free territories for a total of nine years. Scott could not read and had no money, but was helped by his minister, John Anderson. His original owners, the Blows, were among the friends who helped the Scotts through the 11 years of legal battles. Scott lost in St. Louis court the first time the trial was heard in 1847, but that ruling was overturned because hearsay evidence was presented. The Scotts won their freedom in a second trial. Mrs. Emerson appealed the case to the Missouri State Supreme Court, which reversed the ruling and returned the Scotts to slavery. The court ruled that Missouri law allowed slavery and it would uphold the rights of slave owners.

Dred Scott wasn't giving up on freedom for himself or his family. He found a new team of lawyers who hated slavery. The new legal team filed suit in St. Louis Federal Court in 1854. Mrs. Emerson's brother, John F.A. Sanford, who was executor of the Emerson estate, lived in New York, which gave them the option of filing in Federal Court because he lived in another state. The Federal Court ruled in favor of the Sandfords and Dred Scott appealed it to the United States Supreme Court.

Just the Facts

In 1850, Irene Emerson married a northern Congressman, Calvin Chaffee, who opposed slavery. After winning the case in the Supreme Court, the new Mrs. Chaffee turned the Scotts over to the Blows, who gave the Scotts their freedom in May 1857. Dred Scott died of tuberculosis in 1858 and never lived to see the Civil War that was fought after this decision.

Taney's Court was filled with a majority of justices from south of the Mason-Dixon Line. Taney was born in Maryland, where his family owned a tobacco farm and were slave owners. The Supreme Court in a 7 to 2 decision ruled against freeing Dred Scott from slavery for three reasons:

- Blacks, regardless of whether they are free or slaves, are not and could not be citizens.

- Temporary residence of a slave in the free territories did not bestow freedom.

- Congress, under the Fifth Amendment, did not have the authority to deprive citizens of their property. This ruling wiped out the slavery provisions of the Missouri Compromise.

Taney read the court's ruling, which included this finding:

- “[Negros] had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order; and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the Negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold, and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic.”

The case split the Democratic Party, which was in power at the time. The northern faction opposed slavery, while the southern faction supported it. A new faction of the Republication Party had been founded in 1854 to lead the fight to prohibit the spread of slavery. The rift in the Democratic Party caused by this decision helped to fuel the election of Abraham Lincoln, who ran on the Republican ticket. After this election, South Carolina was the first to secede from the Union, followed by the other Southern States, which led to the Civil War.

Excerpted from The Complete Idiot's Guide to The Supreme Court © 2004 by Lita Epstein, J.D.. All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Used by arrangement with Alpha Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.