Movies and Film: Surfing the "New Wave"

Surfing the "New Wave"

The outbreak of World War II was a watershed for the thriving French film industry. During the Nazi occupation, many filmmakers (Jean Renoir among them) fled to Hollywood, where they launched highly successful American careers; others stayed on in Paris and made films that stayed safely away from the eyes of the censors while sometimes embedding hidden anti-German messages in their productions.

Second Take

Though they were often castigated as reactionary and traditionalist by some of the Nouvelle Vague (New Wave) crowd, be sure not to miss Jean Renoir's post-World War II films, especially Elne et les Hommes (1956), Le Djeuner sur l'Herbe (1959), and Le Testament du Dr. Cordelier (1961).

Ironically, as they would in Italy, the oppressive war years made possible the budding careers of a variety of directors, including Robert Bresson (Les Anges du Pch, 1943; Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, 1945), Henri-Georges Clouzot (L'Assassin habite au 21, 1942; Le Corbeau, 1943), and Jacques Becker (Goupi Mains rouges, 1943; Falbalas, 1945).

The Changing of the 'Garde

For France, the 1950s was a period of rebuilding and rethinking. While the bombed and shelled edifices of Paris were being replastered and restored, the well-known directors from the prewar period returned to France and shot some of their most expensive (if in some cases less inspired) films. Ren Clment's Jeux interdits (1952) and Plein soleil (1959) shuttle between wartime melodrama and Hitchcockian suspense, while the German expatriate Max Ophls kicks in with costume dramas like Madame de… (1953) and Lola Monts (1955).

But things were changing in French filmdom. (For better or worse? We'll leave it up to you!) While the mainstream studios picked up production where they'd left off before the occupation, a cadre of young radical artists, writers, critics, and aspiring directors was emerging to challenge the dominance of the entrenched powers in the nation's industry.

Claude Chabrol's Le Beau Serge (1958) and Alain Resnais's great Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) officially launched the Nouvelle Vague, or "New Wave" of French cinema, a movement dedicated to rejecting what were seen as the sappy pretensions of the older generations of filmmakers.

Cahiers du Cinma

Second Take

Don't be a Franco-fool! Cahiers is not pronounced "ku-HEERS," but "ka-HYAY."

What united the main directors of the New Wave more than anything else was a new and immediately controversial journal called Cahiers du cinma. The magazine was founded in 1951 by Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and, more important, Andr Bazin, a brilliant and iconoclastic writer on film who believed that cinema's greatest attribute was its ability to project "objective reality" to its audience without the interference of montage or other messy technical feats. His heroes were American directors like Ford, Welles, Howard Hawks, Otto Preminger, and Sam Fuller, as well as some true "B-movie" directors who never achieved much commercial or artistic success during their careers.

The Cahiers writers valued a director's individuality above all else; their most revered auteurs were not primarily independent directors, but rather those who had carved out a unique cinematic voice for themselves while financed and managed by the big studios. Indeed, it was here, in a famous 1954 essay, that Franois Truffaut launched what came to be called the "Auteur Theory," and the journal's pages were subsequently filled with essays and position papers arguing for the promotion of any number of obscure and previously un-acclaimed directors to auteur status.

In addition to Truffaut and Godard, other writer/directors associated with Cahiers du cinma whose films were deeply influenced by the journal's theoretical stances were Claude Chabrol (Les Bonnes Femmes, 1960), Jacques Rivette (L'Amour fou, 1968), and Eric Rohmer (Chloe in the Afternoon, 1972). The journal, still published today, remains at the forefront of world film criticism and opinion.

True Truffaut

Jean-Pierre Laud as the abused Antoine Doinel in Truffaut's Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows, 1959).

Watching The 400 Blows (1959) is one of the most haunting, moving, and painful cinematic experiences you'll ever have. Franois Truffaut's first feature film was also his most autobiographical, tracing the experiences of an adolescent boy named Antoine Doinel (played brilliantly by Jean-Pierre Laud) as he survives a sentence in a juvenile prison. Truffaut, too, had an extremely unhappy childhood that culminated in grueling work at a factory in his teenage years. After the war, Truffaut's passion for the movies was recognized by a prominent writer on the French cinema named Andr Bazin, who encouraged the cynical young moviegoer to join his growing staff at the offices of Cahiers du cinma.

More than any other French filmmaker, Truffaut used his work to wed film theory and criticism with film production and artistry. Writing slavish encomiums to Hitchcock, the great British auteur, in the pages of his journal while imitating his style in humorous suspense films like Tirez sur le pianist (1960), Truffaut sought to provide filmmaking with a firm historical and intellectual grounding in the past of the art form. One of his greatest and most acclaimed films, Jules et Jim (1961), combines a passionate and technically brilliant meditation on the emotional violence of war (the title characters are, respectively, a German man and a Frenchman fighting it out over a woman they both love on the eve of World War I) with a lyrical sadness that makes the film one of the truly beautiful pictures to come out of the New Wave.

Other Truffaut films to watch include a few shorts, Une Visite (1954), Les Mistons (1958), and Histoire d'Eau (1959), which he codirected with Jean-Luc Godard; the other films featuring Antoine Doinel, such as Baisers vols (Stolen Kisses, 1968), Domicile conjugal (Bed and Board, 1970), and L'Amour en fuite (Love on the Run, 1979); and his great movie about the movies, La Nuit amricaine, which won an Oscar in 1973.

Thank God(ard) for French Film

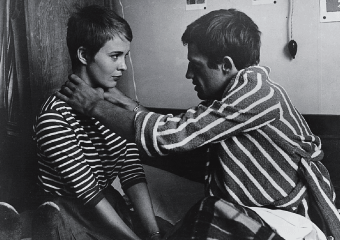

A typically grainy shot from Godard's Bout de Souffle (Breathless, 1960).

Short Cuts

Danish-born model Anna Karina's acting career got off the ground when she met Jean-Luc Godard in the early '60s. After their marriage in 1961, she starred in several of his films during the following years, including Un Femme est une Femme (1961) and Vivre sa Vie (1962).

If Truffaut's contribution to the New Wave was a quiet pathos and a frank look at human emotions, Jean-Luc Godard's career was characterized by riveting portrayals of outsiders and the socially marginal: prostitutes, foreigners, political dissidents, criminals. His low-budget debut feature, Bout de Souffle (Breathless, 1960), was a stunning break from convention. The story of a young Parisian car thief who befriends an American student who ultimately betrays him, Breathless features handheld camerawork, an original screenplay learned by the actors just before filming each scene, and even the use of a wheelchair for tracking. It remains one of the most technically influential films in history. (You know those wiggly, jumpy shots that open every scene of NYPD Blue? It's Godard, plain and simple.)

Many of Godard's films inspired controversy as soon as they were released. Le Petit Soldat, planned for release in 1960, was banned by French censors for three full years because of its largely sympathetic portrayal of an Algerian terrorist. Other groundbreaking films from this period of his career include Une Femme est une Femme (1961), Vivre sa Vie (1962), Les Carabiniers (1963), and La Chinoise (1967).

In 1971, after a close-call motorcycle accident, Godard took a break from narrative in favor of experimentation with explicitly political and ideological film essays. One of the best of these is Tout va bien (1972), which starred Yves Montand and Jane Fonda in a sweeping look at recent changes in French society.

He also went through a long video phase, experimenting with the possibilities of the new medium and producing a number of works that remain unwatched by all but the experts.

Many critics believe that Godard's politics were deeply naive, his turn away from the breathtaking innovations in narrative film that had won him an international following the act of a narcissistic chameleon who took on different political causes at the drop of a hat. But some of his films from the 1970s and '80s—we're thinking especially of gems like Numro Deux (1975), Passion (1982), Prnom: Carmen (1983), and Aria (1987)—deserve much more acclaim than they've received from the purists. Godard gives you decades of filmmaking to enjoy; his career embraces an enormous artistic diversity and creativity that you'd be a complete idiot not to check out!

Second Take

Godard followed up Tout va bien the same year with a really nasty "conversation" film called Letter to Jane, in which he and his collaborator engage in a cruel critique of what they clearly regarded as Jane Fonda's politics of convenience.

Excerpted from The Complete Idiot's Guide to Movies and Film © 2001 by Mark Winokur and Bruce Holsinger. All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Used by arrangement with Alpha Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

To order the e-book book direct from the publisher, visit the Penguin USA website. You can also purchase this book at Amazon.com.