Fiscal Policy and Economic Growth: Of Deficits and Debt

Of Deficits and Debt

Aside from taxes, few topics in economics excite more emotion than deficit spending and the national debt. Citizens decry the fact that the government spends money more than it takes in, but they blanch at the idea of decreased services or increased taxes. Each of the two major political parties accuses the other of fiscal irresponsibility, and in a way, they are both correct.

As of autumn 2002, the national debt totaled $6.2 trillion—a lot of money. Of that amount, $3.6 trillion was held by the private sector and $2.7 was held in government accounts. I'll discuss the growth of the deficit later in this section. First, however, let's look at the two prevailing views of deficits and the national debt. One is that deficits and debt harm the economy, the other is that they don't matter.

EconoTip

Deficits occur when government expenditures exceed revenues. The practice of maintaining or increasing expenditures when revenues will not cover them is called deficit spending. Surpluses occur when government revenues exceed expenditures.

EconoTip

I am lumping the two issues—deficits and the national debt—together in this discussion. This is proper given the reality of the federal budget, which ran a deficit for all but five years from 1960 to 2001 (1969 and 1998-2001). Continual deficit spending has created the $6.2 trillion U.S. national debt.

However, it would also be proper to treat the deficit and national debt separately. That's because a person could believe in the value of deficit spending, but not believe in accumulating a large national debt. In theory, the government could run deficits in years that required economic stimulus and pay that debt down with surplus revenues in years of expansion. But, as I said, that's in theory. It has certainly not been tried.

Stay Out of Debt!

People who believe that deficits and the national debt do matter point out that …

- Continual deficit spending displays lack of fiscal discipline on the part of the government and on the part of the citizens, who want government goodies without having to pay for them.

- This lack of fiscal discipline spills over into the private sector, where households and businesses have become “addicted to debt.”

- Interest payments on the national debt represent a substantial claim on tax revenues that could be better spent on other things.

- Future generations will bear the burden of today's debt and either have to pay the interest on it or pay down the principal, or both.

- Deficit spending and high debt limit the government's fiscal policy options: If deficit spending is the norm, how much more (deficit) spending will be needed to stimulate a sluggish economy?

- Foreign entities now hold about $1 trillion of U.S. government securities. If their willingness to buy or hold that debt diminishes, we would have to absorb it.

These points are hard to contradict, except perhaps for the last one: Foreign entities seem to enjoy the safety, liquidity, and interest rates provided by U.S. government securities.

No, Debt's Okay!

The arguments in favor of continued deficit spending and high national debt are:

- The size of the national debt or budget deficit is not an indicator of the condition of the economy. Other factors, such as growth, productivity, employment, and price stability, are all more important. The entire issue is one of politics, not economics.

- We owe the debt to ourselves (mostly) and therefore should not be overly concerned about paying it back. Also, we pay the interest on the debt mainly to ourselves, and that money remains in the economy.

- While the burden of the deficit is passed on to future generations, so are the Treasury securities and, more important, the assets financed with the debt.

- The deficits and the national debt have not grown substantially relative to other measures of the economy's magnitude, including GDP, total income, and total assets in the economy.

- Paying down the national debt is not something the nation has to do because the debt can be rolled over indefinitely—that is, continually refinanced by issuing new government securities.

- Deficit spending has helped the nation to establish a solid baseline level of demand and has contributed to the outstanding U.S. record of economic growth.

Economists' Two Cents' Worth

Elected officials, candidates for office, and the public tend to move between the two poles. Economists themselves view the issue as quite complex, but on balance generally believe that …

- Future generations bear an unfair burden if the debt being passed on to them is not accompanied by a corresponding level of productive capital.

- Debt in foreign hands sends money out of the country, but this may be offset if the debt is used to finance capital that produces additional income.

- We make the interest and principal payments (mostly) to ourselves. However, these amount to transfer payments when the people paying the taxes are not the same as the people holding the securities and receiving the interest and principal payments.

- Indefinite and unbridled deficit spending can lead to inflation and, potentially, economic instability. It can undermine credibility in the government's ability to manage the economy.

The Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman (who you will meet) said it best: “There is no such thing as a free lunch.” Is it conceivable that each generation of citizens could consistently demand more public goods and services than they are willing to pay for and generate no economic consequences? Doesn't the situation looming ahead for Social Security (described in Hey, Big Spender! The Federal Budget) indicate that even the government can run out of rope? Might an aging population find itself unable to handle the level of debt the nation continues to incur? Also, how much of that debt has actually gone into productive plant and equipment? Our review of the budget in Hey, Big Spender! The Federal Budget showed that most of the budget, if not the deficit, is in fact not going into productive plant and equipment.

Also if interest rates increase, won't the interest payments on the national debt—which now consume 11 percent of the budget—rise? In the late 1970s, they accounted for 14 percent of the federal budget.

A Look at the Recent Record

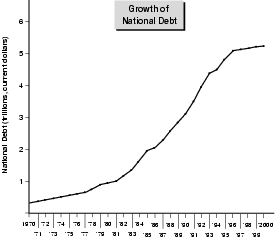

Figure 13.3 provides some historical perspective on how the U.S. national debt reached $6.2 trillion.

(Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury)

From 1970 to 2000, the national debt rose from $389 million to $5.7 trillion, a more than thirteen-fold increase in 30 years. In the preceding 30 years, which included World War II and the mobilization for the war in Vietnam, the national debt rose from $43 million to $389 million, an eight-fold increase.

The largest sustained increase in the national debt occurred from 1980 to 1992, when it rose from $930 million to $4 trillion. Ironically, this is the period of the administrations of Ronald Reagan (1980-1988) and George H. W. Bush (1988-1992)—ironic because Republicans had long been associated in the public mind with fiscal responsibility. Indeed, President Reagan regularly spoke of “those tax-and-spend Democrats.” The program of his administration was to “spend and borrow” after cutting taxes. As a result, the national debt tripled during his two terms. Yet President Reagan's strategy for igniting strong growth worked.

As I mentioned earlier, the 1970s had been a period of stagflation: slow growth along with high unemployment, high interest rates, and high inflation. The economic stimulus provided by President Reagan's tax cut in August, 1981—which scaled back marginal tax rates by 25 percent over three years—clearly set the economy on a growth trajectory.

But it also set the national debt on a growth trajectory. The debt rose from $930 million in 1980 to $2.6 trillion in 1988. Some observers point out that this doesn't matter because after the tax cut, government tax receipts doubled from about $500 billion to $1 trillion from 1980 to 1990, due to the higher income in a growing economy. But whatever the increase in tax receipts, it clearly did not come near to covering the increase in government spending—for which each party blames the other.

Democrats enjoy taking credit for the slower growth of the national debt from 1992 to 2000, President Clinton's administration. During that period, the debt increased from $4.1 trillion to $5.7 trillion, or by 39 percent, well under the almost 300 percent of the Reagan administration. However, the Clinton administration had two things going for it: First, from 1992 onward, the economy grew even more rapidly than it did in the 1980s. Tax receipts rose dramatically, generating budget surpluses from 1998 through 2001. Second, inflation and interest rates remained at historical lows, and the monetary policy that partly engineered that phenomenon clearly contributed to the length and growth rate of expansion. (President Clinton wisely reappointed Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, twice.)

The Clinton administration also benefited from a new focus on fiscal discipline in both parties, prompted by the deficits of the 1980s. Groups like the Concord Coalition and individuals like Ross Perot—who based his quixotic presidential campaign on deficit reduction—were emblematic of this concern. In 1990, President George H.W. Bush even agreed to a tax increase. It was politically difficult given his famous campaign promise: “Read my lips: No new taxes.” Recession followed in 1991, and given the reaction of the public, candidate Clinton won the presidency in 1992.

Some observers trace the expansion of the 1990s to President Clinton's tax increase in 1993, which boosted rates on the wealthiest households. The credit may be misplaced, yet the tax increase certainly didn't hurt the economy, and may well have helped.

Wait! How could a tax increase help a recovery? Isn't a tax increase supposed to cool a recovery by lowering disposable income?

Ordinarily, yes. However, with the deficits and debt at high levels, some economists believe that “crowding out” and high interest rates hampered the growth of investment at the time. Crowding out occurs when government borrowing makes it harder for the private sector to obtain funds. The resulting competition for the nation's savings also increases interest rates.

The logic of the 1993 tax increase bolstering the expansion is that the financial markets saw it as a harbinger of declining deficits and lower interest rates. Indeed, deficits and interest rates both did decline in the mid-to late-1990s, and investment soared to record levels. It's quite possible that the financial markets and the business community responded positively to the tax increase. Again, it certainly did not hamper the recovery.

Excerpted from The Complete Idiot's Guide to Economics © 2003 by Tom Gorman. All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Used by arrangement with Alpha Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

To order this book direct from the publisher, visit the Penguin USA website or call 1-800-253-6476. You can also purchase this book at Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble.