International Finance: About Foreign Exchange

About Foreign Exchange

As you know, money is anything that is accepted as a medium of exchange. In most of the world, people accept pieces of paper imprinted with pictures of national heroes or local wonders of nature as money. But in each nation, they accept different pieces of paper.

This means that if someone in the United States wants to buy something from someone in, say, Mexico, she must first exchange her local currency—dollars—for the currency accepted in Mexico—pesos. This currency conversion occurs at an exchange rate.

The exchange rate—the price of one nation's currency in terms of another nation's—is a central concept in international finance. Virtually any nation's currency can be converted into the currency of any other nation, thanks to exchange rates and the foreign exchange market. For instance, let's say the current exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and the Mexican peso is $1 to 10 pesos. This means that $1 will buy 10 pesos and that 10 pesos will buy $1. (I am ignoring transaction costs, such as the commission charged by the bank or foreign exchange broker who does the currency conversion.)

EconoTalk

Currency conversion is the procedure of changing one currency into another currency. The exchange rate is the ratio by which one currency is converted into another. It is the price of one currency expressed in another currency. Exchange rates are necessary because currencies have different values relative to one another.

The foreign exchange market includes the importers, exporters, banks, brokers, traders, and organizations involved in currency conversion. The FX or FOREX market, as it is called, is not a physical place—though many participants work in offices and on trading floors—but rather the entire network of participants in the market.

Importers and exporters need foreign currency in order to complete transactions. Banks and brokers maintain inventories of foreign exchange, that is, various currencies, and convert currencies as a service to customers. Traders and speculators make (or lose) money on the movement of foreign exchange rates (which I'll describe later). As you will see, central banks also play a role in the foreign exchange market.

Types of Exchange Rates

Foreign currency exchange rates have historically been determined in three different ways:

- Fixed rates

- Floating (or flexible) rates

- Managed rates

With a fixed exchange rate, the value of the currency is determined by the nation's central bank and held in place by central bank actions, mainly the purchase and sale of the currency. Another way to fix exchange rates, which has been used by the United States and other nations in the past, is to tie currencies to the gold standard. If all the currencies in the exchange rate system have a value pegged to gold, it is a simple matter to convert the currencies to one another according to their value in gold.

Floating exchange rates are determined by the market forces of supply and demand. We will examine these forces in this section. Essentially, if demand for a currency increases, the value of that currency in terms of other currencies increases. If demand for the currency decreases, then the value of the currency decreases.

Managed exchange rates are influenced by nations' central banks, but are not targeted to a fixed rate. In practice, the system of managed rates that we have today operates through the forces of supply and demand and are influenced by central banks. So we now have a mix of floating and managed rates, which is called managed float.

Foreign Currency Supply and Demand

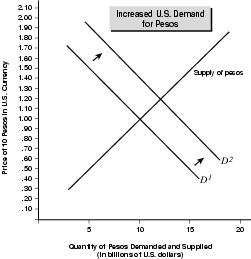

The economic forces that determine foreign exchange rates are rooted in supply and demand, both of which are determined mainly by foreign trade activity. For instance, if Americans increase their demand for products from Mexico, Americans will need to buy more pesos in order to buy those Mexican products. Thus an increase in U.S. demand for Mexican imports will increase the demand for pesos. The dynamics are illustrated in Figure 18.1.

An increase in the demand for any item, including currency, will increase its price. As we see in Figure 18.1, that is the case when Americans demand more pesos. The increase in the demand for pesos from $10 billion worth to $12 billion worth increased the price of pesos. Where $1.00 used to buy 10 pesos, after the increase in U.S. demand for Mexican imports—from $10 billion worth to $12 billion of Mexican goods—it takes $1.20 to buy 10 pesos. Put another way, a peso that used to cost 10 costs 12 after the increase in demand.

EconoTip

Business news reporters often employ colorful turns of phrase to describe economic events, but the terminology can be confusing. When a reporter states that the ”dollar rallied” in that day's trading, it means that the dollar (or whatever currency is being discussed) strengthened against most currencies. When a reporter says there was a “sell off” of the dollar or that the dollar “was attacked,” it means that the dollar weakened against most currencies.

In this situation, the dollar is said to have depreciated against the peso. Other ways of stating this are to say that the dollar lost value, lost ground, or weakened against the peso. This sounds worse than it is. All it means is that the United States demanded more imports from Mexico. But this kind of language is used for a simple reason: The dollar buys less than it used to in Mexico. After the increase in the peso to dollar exchange rate, it takes $1.20 to buy what $1.00 used to buy in Mexico.

Given the law of supply and demand, this only makes sense. When Americans demand more Mexican products, they bid up the price of those products. When that occurs, the exchange rate mechanism adjusts itself to reflect that price increase. Therefore, the price of the peso, and thus of Mexican goods, rises.

Let's look at this from Mexico's point of view. If the dollar has depreciated—lost value, lost ground, and weakened—against the peso, then the peso has appreciated—gained value, gained ground, and strengthened—against the dollar. While this makes Mexico's products more expensive for Americans, it also makes U.S. products cheaper for Mexicans. The effects of the changes in two currencies mirror one another.

Excerpted from The Complete Idiot's Guide to Economics © 2003 by Tom Gorman. All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Used by arrangement with Alpha Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

To order this book direct from the publisher, visit the Penguin USA website or call 1-800-253-6476. You can also purchase this book at Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble.